|

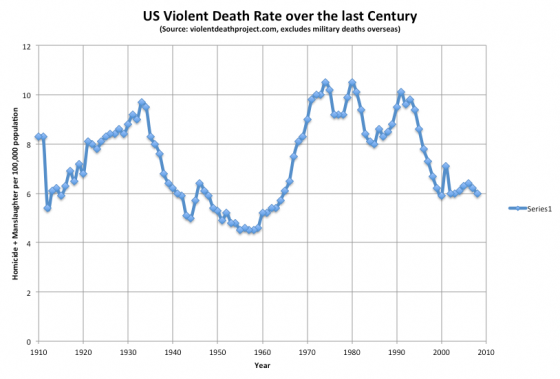

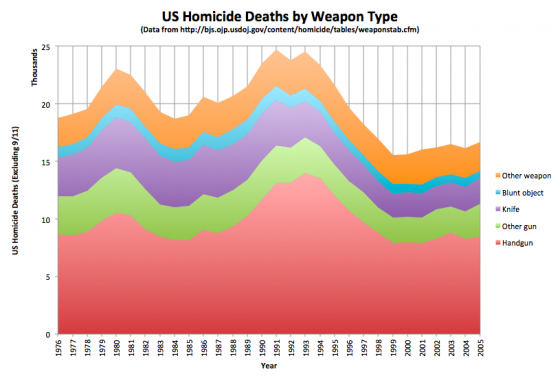

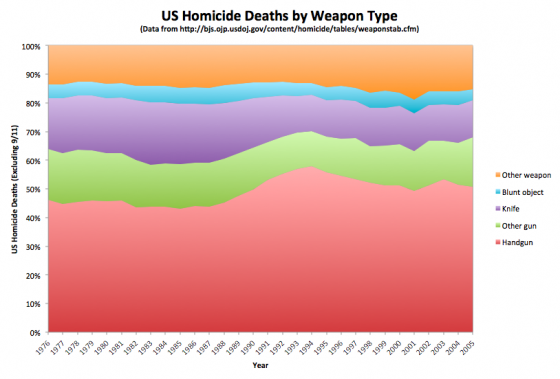

Like many people, after I heard the news about the school shootings in Connecticut, I spent time watching the news come in, I spent time reading about it, and I was very emotionally effected by the whole thing. I admit I cried. Each time I thought about it, I couldn’t help thinking about the families, and imagining the incredible pain if something like that were ever to happen to my own family. It was an incredibly sad day. At the same time though, I hear the repeated “we must do something!” calls, and while I emotionally empathize with them, I also get very frustrated. Because as tragic as this all is, there are a few things to remember, and if you are going to look rationally at these kinds of things, especially if you are going to start talking about laws and political solutions, then you need to step back a bit. So lets start: 28 people killed at one time is NOT worse than 28 people killed separately. It is more visible. It is more shocking. I have heard it said that when multiple people are killed together it has the same emotional impact as if that number of people SQUARED had been killed separately. So 28 people killed together has the emotional impact of 784 people killed separately. Perhaps so, but in the end, 28 people are still dead either way. Yes, it was horrible that 28 people were killed yesterday, and it was horrible that most of them were children. But every year there are over FIFTEEN THOUSAND people killed violently in the United States. And over SEVEN HUNDRED of them are children under 14. (Source: DOJ) As dramatic and disturbing as the deaths of those 28 people are, it is a drop in the bucket compared to the overall rate at which people are getting murdered in the United States. (And according to the DOJ only about 1 in 2000 homicide incidents involve 5 or more victims and 95% of all homicides have only a single victim.) If you are going to set policy to try to reduce violent death, if you try to craft a policy that is specifically structured to address statistically rare mass killings, then even if you succeed in reducing the frequency of THESE events, you will not actually be optimizing for reducing TOTAL violence and therefore you would NOT be doing the best you could for the public. So what does the violent death rate look like? Using numbers from violentdeathproject.com: Dramatic improvements were made throughout the 1990’s. Since then, with the exception of the peak from 9/11 in 2001, the violent death rate has been essentially flat. (The most recent data here is 2008, as these things have a bit of lag. There is evidence for a further DROP since then, although that second source includes fewer deaths in their numbers than VDP since VDP includes manslaughter as well as homicide.) So while there is still TONS of room for improvement… The US rate of 6.1 per 100k is horrible compared to most of the rest of the developed world… 1.9 per 100k for Germany, France and Canada; 1.3 per 100k for the UK; 0.8 per 100k for Japan… things HAVE generally been moving in thew right direction in the last couple of decades. You are less likely to be killed violently now in the US than any time in almost 50 years. You have to go back to the mid-1960’s to be better off than today. That does NOT mean that we should not try to do better… that we should not be looking at ways we might be able to reduce the US violent death rates to the levels in the UK or Japan… or better. We absolutely should. We should not by any means accept the idea that the US is just more violent and that is OK. But it does mean when you hear breathless comments about how out of control things are, and how desperate the need is for “immediate action”, you should take a deep breath and look at things in the larger context. Now, the next thing to look at is type of weapon used. The conversation has immediately turned to gun control, but should it? Lets look at two relevant charts, this time the source of the data is the Bureau of Justice Statistics at the DOJ. Unlike the VDP data, these only include homicides (not manslaughter), and exclude 9/11.

These two charts show the same data, but one with absolute numbers, and the other as a percentage of total homicides. It stands out immediately that about 2/3 of US Homicide deaths are indeed committed with guns. That is an extraordinarily high number. The only real change here seems to be an reduction in the number of murders committed with knives over the time frame shown, both in absolute and percentage terms. (Anybody know why that happened? Why are knives less popular than they were?) This seems to indicate that if you want to reduce the overall homicide rate, targeting gun violence is actually a pretty good place to start. There is of course the argument that if guns were not available, or at not as easily available, that many of those murders would still happen, people would just use different weapons. And of course even with restrictions, anybody who really wanted a gun could still get one. Both of these points are true. But because the percentage of violent deaths by gun is so high, even if a small percentage of the homicides did not happen because the perpetrator couldn’t get easy access to their weapon of choice, it would make a significant difference to the overall rate. Of course, that doesn’t say what actual policies might or might not help. It is quite easy to construct policies that are very restrictive, but have no actual effect on public safety, or which may actually reduce safety when you take everything into account. (See, for instance, TSA policy at airports and how people driving more after 9/11 caused an increase in highway deaths.) So even if you do engage in gun regulation, you need to be careful about what you do in order to ensure that you actually are effective at changing anything regarding the violent death rate. And perhaps more importantly, that you don’t also introduce significant and unacceptable restrictions in personal freedom that have other negative side effects. But a perhaps even more salient point, the most effective way to reduce the overall rate of violence may have NOTHING to do with restricting weapons of any sort. Rather, I have seen some arguments that massively increasing availability and access to mental health support would have an even bigger effect. Easily available inpatient care to those who need it of course, but even more than that, just options and support for those who are in stressful situations that could escalate, or to those with conditions that make them more likely to react violently to provocations. So even though additional gun control MAY be an effective part of a plan to help improve the violent death rate, any discussion about this sort of issue should not be exclusively about gun control, or about reacting to “mass killings”. Anything that is done needs to take a broader perspective, looking at the overall violent death rate and long term trends. Any knee jerk reaction that is highly focused on a specific incident, or even types of incidents, is very likely to be ineffective or even counter productive at solving the larger problem. [Edit 2012 Dec 12 20:36 to correct a place where I accidentally said “drug” instead of “gun”. That’s a whole different can of worms, although of course drug policy also has an effect on the death rate.] |

||