The massacre in Orlando this weekend is horrifying. I mourn along with everybody else.

On Twitter and Facebook people are predictably sorting themselves into either those who are using this as an opportunity to talk about how awful mass shootings are and how therefore we need to ban assault weapons vs people who are using this as an opportunity to talk about how horrifying terrorism is and how therefore we need to double up on the “war on terror” (in many cases with a fairly anti-Muslim orientation). A whole range of reactions is on display relating to how this specific attack was targeted at the LGBT community as well.

In the face of this, I always want to step back a bit and look at the bigger picture.

First of all, while mass killings understandably wrench the emotions differently and more strongly than individual killings, in the end, 50 people dying together is not worse than 50 people dying individually. They are equally tragic. But aside from the immediate families of those involved, the 50 people dying individually is more invisible to us as a society, so it tends to get ignored. The extra attention given to the incidents when many people are killed at once is understandable, but it also distracts from the magnitude and nature of the real problem. Mass killings make up an incredibly small portion of overall homicides. Concentrating on them will inevitably lead to people going after the wrong things when looking for solutions.

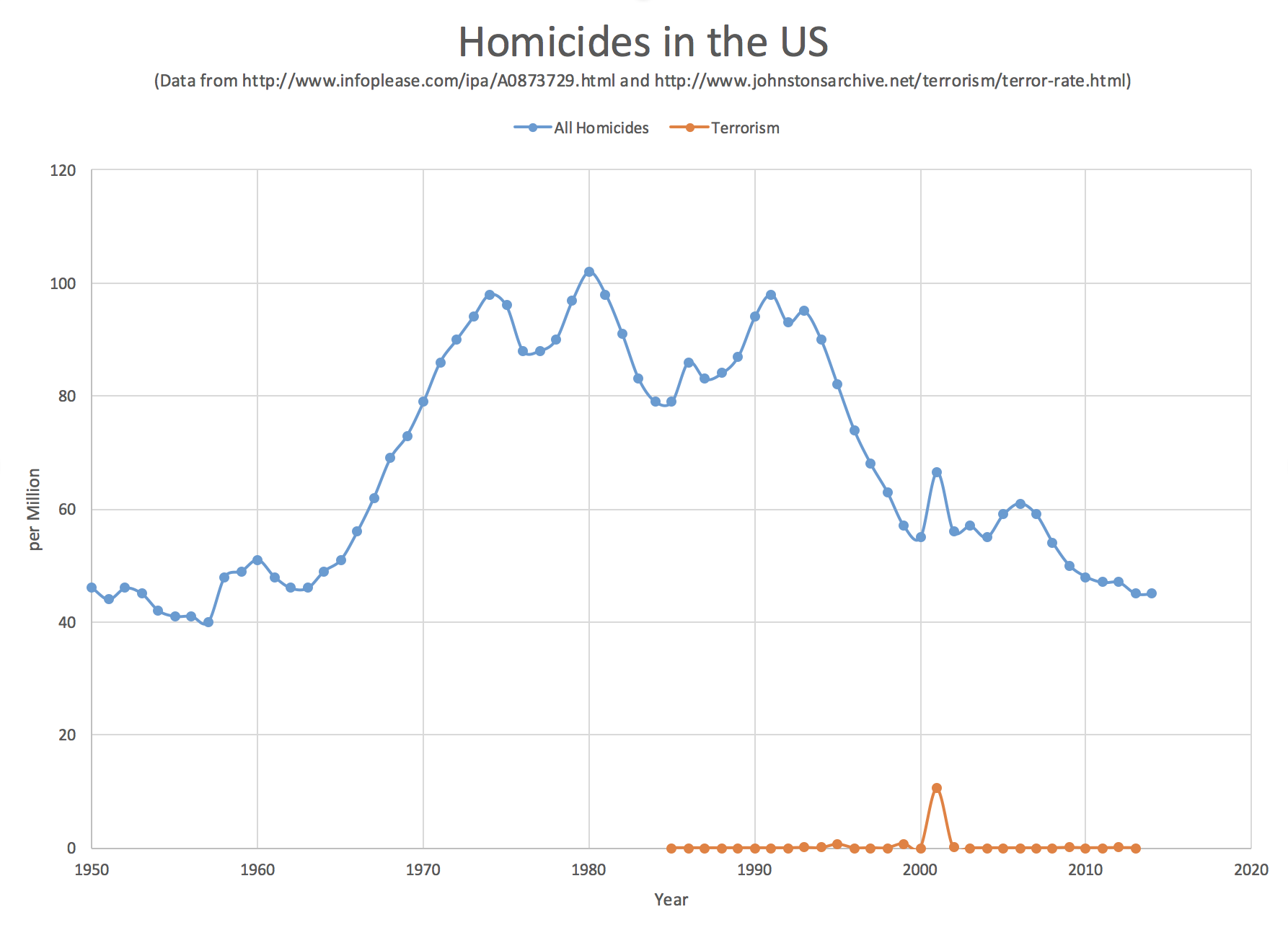

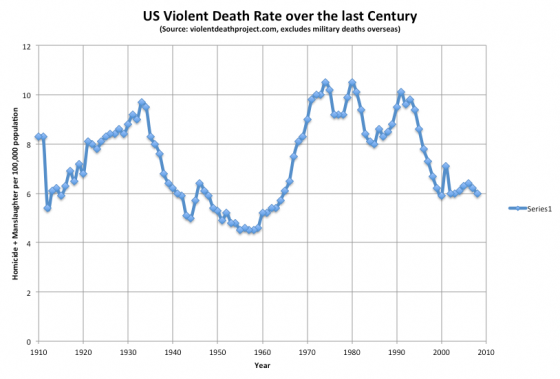

Second, yes, murders are a problem. Yes, the United States has a higher murder rate than comparable countries. Much higher. And we should be able to do much better. But… look at that chart above. The homicide rate nation wide has been DROPPING for decades. It is about half what it was in the 1980’s. The trends are going in the right direction. We are much safer than we were. From the frenzy whenever one of these attacks happens, you would think that we had a problem that was worse than it ever has been and was getting worse rapidly. No. We may have a long way to go to match our peer countries (19 per million for Germany, France and Canada; 13 per million for the UK; 8 per million for Japan, compared to 45 per million for the US) but we have been headed in the right direction for many years now. Things are getting better, not worse.

Third, with the notable exception of 9/11, deaths caused by terrorism in the United States are almost invisible compared to the rate of all homicides. Yes, it is horrible when a terrorist attack happens. Boston and San Bernardino and now Orlando are shocking. They disturb our sense of safety in a way that isolated killings do not. It is even more pronounced when the attacks specifically target one community, as the Orlando event targeted the LGBT community. The psychological effects of such attacks on the nation and on the targeted communities is real and should not be ignored. Responses though need to be proportionate to the problem, or they end up being like an allergic reaction, causing more harm through the response than the problem they are trying to solve. Even including 9/11, terrorist attacks were responsible for only approximately 0.6% of homicides from 1985 to 2013. I am of course not saying such attacks should be ignored in our policy, but I am saying that our response to these sorts of attacks, both in how the public reacts and in how policy changes as a result, is horribly disproportionate to the actual problem.

All in all, I wish people on all sides of these debates would take a step back from their emotionally charged initial reactions, and the sorting into political tribes they will defend regardless of the issue, and instead actually try to look at things in a facts based way, and if looking to solve problems, try to base solutions by actually trying to determine what might be most effective at moving the needle on the overall metrics.

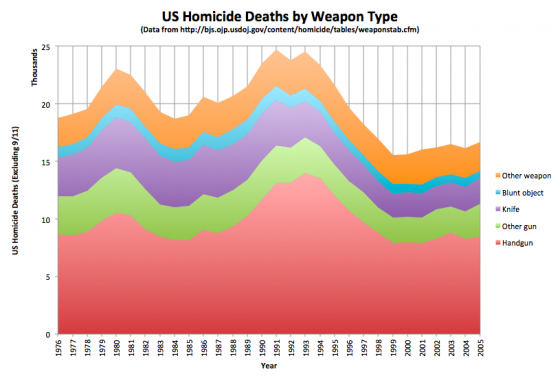

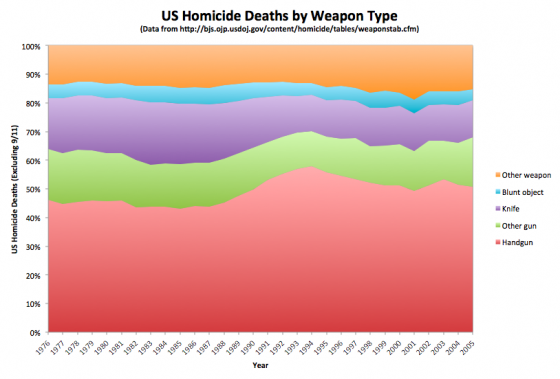

So, for instance, banning assault weapons probably won’t make a big difference, because they are responsible for a really small portion of overall homicides. Focusing on them is a distraction, despite the high profile of the events they are involved in. Focusing on “Islamic Terrorism” will likely not help much either, as that too is responsible for small numbers in comparison to other motivations.

Meanwhile, making it overall a bit more difficult to get handguns might indeed reduce the numbers noticeably. But that would involve making a lot of people feel like you are taking away a fundamental right, which should also be factored into any cost/benefit analysis. It should not be ignored or dismissed. Solving one problem by making a huge portion of the population feel that you are attacking their fundamental values would just create other problems, possibly worse ones. Making long term changes to the culture so fewer people want weapons in the first place might work, but is something that would happen over many decades, and there is little patience for that. Working on anger management and conflict resolution skills as part of basic education might help quite a lot too, although is also something that takes a long time to show results. Increasing resources to identify and help people who are under stress, who are showing signs of becoming violent, or who have untreated mental illness that is a danger to themselves or others would surely make a big difference as well.

I don’t specifically claim to have the answer or the right mix of answers. I’m not specifically advocating any policy option. The above is just an off the top of my head look at a few options that people sometimes mention. The key is that I wish that people would look at the various options rationally, looking at the numbers and keeping an eye on the big picture, as well as taking into full account people’s concerns about rights and worries about safety. Violent death and homicide are problems that are approachable through analysis and experiment. We can see what works, and what doesn’t work. Both by trying things and observing things other countries have tried. We should be open to investigating the possibilities, and to experimentation. Keep what works, ditch what doesn’t.

But alas, this is the real world, so that won’t happen. Instead we will focus on highly visible incidents that aren’t representative of the overall problem, and everyone will focus on the problems and solutions their tribe tends to focus on, and will continue believing that the people on the “other side” are crazy or evil or just don’t understand, and the only thing that will happen is that the polarization of society will increase further.

Sigh.

(I did a somewhat similar post after Sandy Hook if anybody wants to review what I said then, and in that one I also talked about killings using guns vs killing using other weapons, something I chose not to revisit this time.)